Hello :) This newsletter is all about beech trees but before I get into it: I’m bringing herb, dye flower, and veggie starts to this fundraiser plant sale on Sunday. 100% of sales go to a Palestinian family rebuilding their farm in Gaza. Share with your western mass friends or come by if you’re local!

Remember when a huge black bear ran across my path? After that peak experience, I couldn’t get black bears out of my head. Their diet is mostly plants, in spring they eat skunk cabbage to flush their digestive systems (and they are the only mammals who can stomach the raw plant), they have a unique reproductive adaptation called “delayed implantation” (imploring you to look into it) - my mind became a trap for bear facts. Eventually I heard one that stopped me in my tracks: in northern New England, black bears rely so heavily on beechnuts for fat and protein before winter that the reproductive cycle of the bear mirrors the reproductive cycle of the beech tree. Black bears even climb beech trees to make nests where they can hang out and eat beechnuts from high up branches. My immediate thoughts: 1. wow and 2. isn’t something bad going on with beech trees right now?

And then I was assigned a semester long research paper. I chose to research the current status of the American beech tree with a focus on implications for wildlife, specifically the North American Black Bear. This ended up being a hugely fascinating (and admitadly distressing) topic. Several of the studies I read in my review of the literature were published in 2024 and 2025 - we are currently learning a lot about the diseases affecting our beech trees. I’m about to share some condensed excerpts from my paper that hit the main points of what is happening with our beloved beeches. If you want the full paper that goes deeper into each disease and forest dynamics on the whole, reply to this email and I’ll be happy to share it. That version also has in-text citations. I hoped to make this version more readable for a more casual peruse and you can still find a full list of my references at the end.

The American beech tree (Fagus grandifolia) is a large, deciduous tree native to Eastern North America. Many species of wildlife depend on the tree, from the North American black bear to the endangered early hairstreak butterfly. There are four main adaptations that have allowed F. grandifolia to become a key species in northern New England’s hardwood forests: shade tolerance, vigorous clonal shoots, low sensitivity to soil acidity, and relative resistance to deer browsing. The range of the American beech extends from Nova Scotia to northern Florida and west to Texas. It has a light gray bark that is smooth and among the thinnest of all the trees in New England. The buds are narrow with overlapping scales. The leaves are elliptical with pointed tips, coarse teeth, and are pinnately veined. They are three to four inches long and have alternate arrangement along the branch. Beech trees are monoecious, wind pollinated, and produce a mast crop of highly nutritious beechnuts. Beech trees typically live 300-400 years, with individuals known to reach 500 years. Beeches are shade tolerant and can spend a century or more in the understory waiting for a gap in the canopy, at which point they can shoot up to heights of 60-100 feet and reach a trunk diameter at breast height of up to 98 inches.

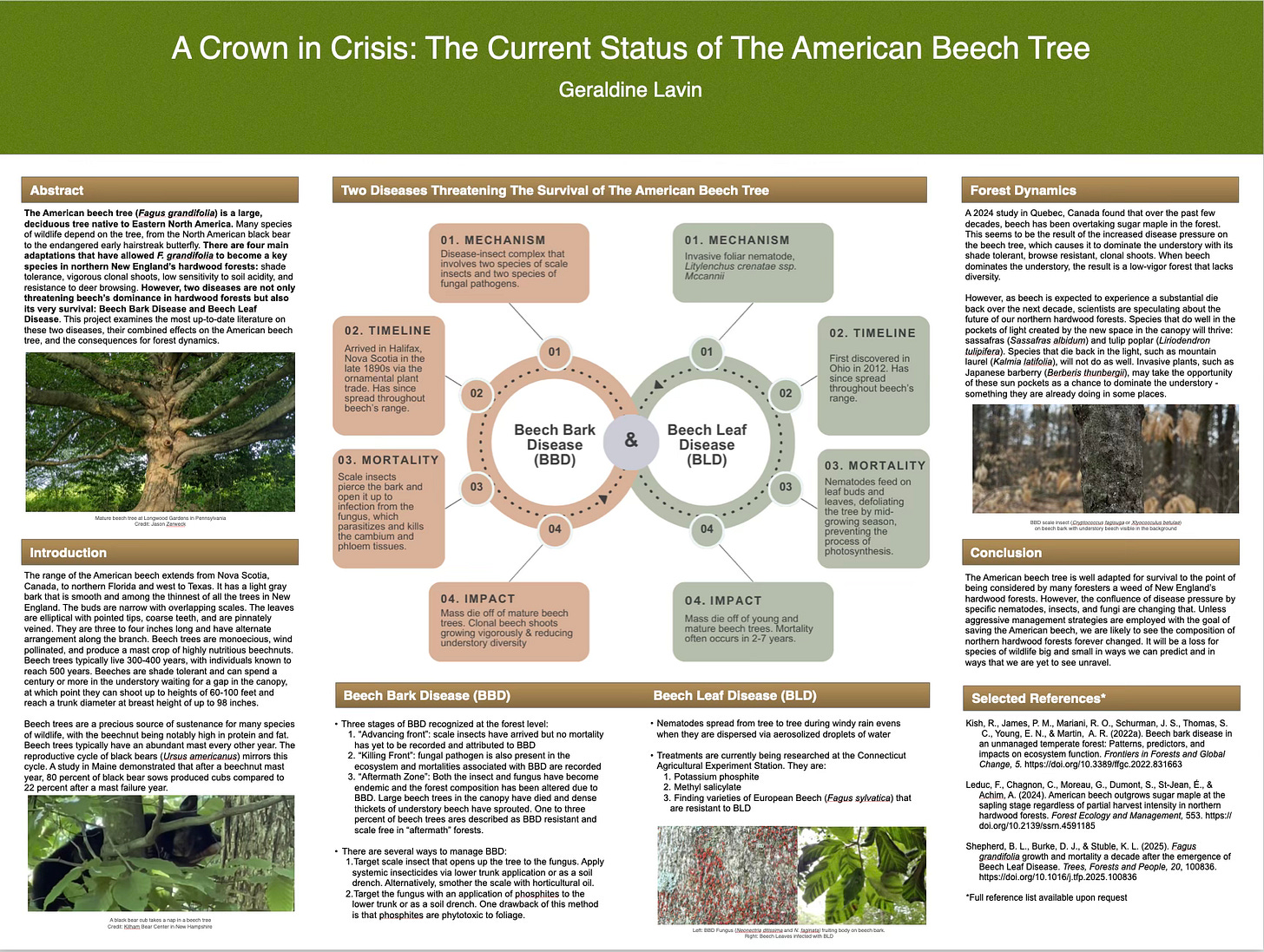

There are two diseases that are threatening not only beech’s dominance in hardwood forests, but its very survival: Beech Bark Disease and Beech Leaf Disease.

What is known as Beech Bark Disease is actually a disease-insect complex that involves two species of scale insects and two species of fungal pathogens. Both native (Xlyococculus betulae) and non native (Cryptococcus fagisuga) insects pierce the bark, opening up beech to the fungi which kill it by parasitizing the cambium and phloem tissues, eventually girdling the tree. The fungi involved are the non native Neonectria faginata and the closely related native fungus, N. ditissima. The non-native scale insect and fungal pathogen involved in this complex were introduced to Halifax Public Gardens of Nova Scotia, Canada in the late 1890s by way of imported European beech trees (Fagus sylvatica). The thin bark of the beech tree makes it uniquely vulnerable to insect scale damage. In a study published in 2022, Canadian scientists found that the infection rate for all beech trees across North America was 80-95 percent. They estimated that Beech Bark Disease will have spread through beech’s entire North American range by 2025.

Beech Bark Disease spreads by scale insect larvae dispersing downwind from the trees. The distance depends on the wind speed and height of the tree, with the average distance being about 10 meters for a wind speed greater than 1 meter per second. However, 1 percent of larvae get caught in airstreams above the canopy and can travel longer distances at greater speed. After the beech scales pierce the bark of the tree, it typically takes 1-3 years for fungal pathogens to infect the tree, though sometimes it takes longer. Tree mortality can occur as early as one year after fungal infection.

Beech Leaf Disease was first discovered in North America in Ohio in 2012. It is characterized by discoloration, striping, and necrosis of the foliage with limbs fully defoliated by mid-growing season. Subsequently it has spread to 15 states across the eastern United States and Canada. The early spring damage to the leaf bud and leaf affects the tree's ability to photosynthesize for the rest of the season, which is catastrophic for the tree's ability to produce energy to feed itself. Beech Leaf Disease is caused by an invasive foliar nematode, Litylenchus crenatae ssp. Mccannii. The nematode that causes Beech Leaf Disease was identified in 2017. It is believed to have come from Japan, where scientists have found a similar nematode that is genetically almost identical. L. crenatae is visible to the naked eye but so small that it is better observed using a microscope. The nematodes resemble tiny flailing worms. They feed by puncturing the leaf or bud tissue with a retractable stylet which they use to nourish themselves with the sugars they find there. They reproduce vigorously both sexually and parthenogenetically and it has been reported that 50-60,000 nematodes have been found in one leaf alone. Researchers were unsure how exactly the nematode was spreading from tree to tree until a study published in 2024 unlocked the mystery. Richard Cowles's research shows that a primary mechanism of transport for L. crenatae is wind, specifically the nematodes are spreading during windy rain events when they can be blown from tree to tree in tiny aerosolized droplets of water. This is illustrated in the way that the spread of Beech Leaf Disease seems to mirror the prevailing wind direction: eastward and then north along the coast. Nematodes are also able to travel from tree to tree by way of bird feet during rain events. The migration from tree to tree begins in mid-July, several weeks earlier than scientists had previously thought. The migrations can last well into the autumn season. The findings of a study published in 2025 suggest that beech trees die within 2-7 years of becoming infected with Beech Leaf Disease.

Beech Bark Disease and Beech Leaf Disease each threaten the future of the American beech tree at different stages of its life cycle. When they occur in the same forest, the threat is insurmountable. Beech Bark Disease primarily affects mature beech trees, causing the trees to sprout dense thickets of up to hundreds of clonal beech tree offshoots as a stress response. These clonal offshoots reduce the abundance and vitality of other forest species, lowering overall biodiversity and strength of the forest ecosystem they occupy. Beech Leaf Disease is observed in all stages of beech trees but seems to primarily affect younger trees. The result of these two diseases, which are increasingly occurring in the same forests, and even in the same trees, is devastating for the future of F. gradifolia.

Beech trees typically have an abundant mast every other year. The reproductive cycle of black bears mirrors this cycle. Stacy McNulty, associate director of research at SUNY ESF, explains that the masting schedule of the beech tree ripples out and has measurable effects on the wildlife of the forest. A study in Maine demonstrated that after a beechnut mast year, 80 percent of black bear sows produced cubs compared to 22 percent after a mast failure year. The cycle of beech mast years and low production years are normal, but recently the low production years are becoming more frequent. A drastic reduction in natural food sources means that mother black bears are engaging in risky behavior to put on necessary weight for winter. They are visiting dumpsters, chicken coops, and garages. In New Hampshire, bear-human conflicts were up 65 percent in 2022 compared to the previous five year average. That year, which recorded a widespread beech mast failure, saw a 44 percent increase in bears struck by vehicles and a 38 percent rise in homeowners shooting bears. A study in a snowy region of Japan that shares some characteristics with the landscape of New England explored the relationship between the Japanese beech tree (Fagus crenata) and Japanese black bears (Ursus thibetanus japonicus). The study was conducted in response to increasing human-bear conflict as a result of Japanese black bears entering human settlements due to Japanese beechnut mast failures. The 15 year study found that bear behavior could be predicted by beech inflorescences. In years when there was minimal flowering in summer, there were greater bear intrusions in autumn. In years when the flowering was plentiful, there was minimal to no bear intrusions. The scientists believe that in years when there was mast-failure, the bears were going into the human settlements to expand their range and seek out alternative food sources. As a result of this study, bear intrusion likelihood can be predicted in early summer by observing the flowering pattern of the beech. When the northernmost American beeches die off, we should expect to see changes in the behavior of the wildlife who depend on the beechnut, notably the North American black bear.

The American beech tree is well adapted for survival to the point of being considered by many northern foresters a weed of New England’s hardwood forests. However, the confluence of disease pressure by specific nematodes, insects, and fungi are changing that. The synergistic impact of Beech Bark Disease and Beech Leaf Disease, targeting different life stages, calls into question the future of Fagus grandifolia. Without aggressive and widespread management interventions, the mass die-offs predicted in the coming years will reshape the composition of our forests and disrupt intricate ecological relationships. The loss of beech's nutritious hard mast, particularly in northern regions, threatens the well-being of iconic wildlife like the North American black bear, potentially increasing human-wildlife conflict. The fate of the American beech serves as a stark reminder of the vulnerability of even the most resilient species in the face of introduced pathogens and underscores the urgent need for continued research and proactive conservation efforts to safeguard the biodiversity and ecological integrity of our forests.

Feel free to email me for a copy of the whole paper with citations in the text. I left a lot out of this write up to make it considerably shorter and more readable, but there is plenty more context and nuance to explore in the paper if your interest is piqued. My references are listed at the end of the newsletter.

Thanks for reading! Feel free to comment questions and thoughts about beech trees and black bears - you know I’d love to chat about it. And if you’ve made it this far: click the heart or leave a reply! I love when you engage with my writing O:)

++

Geraldine

References:

Ahrens, J. (2024, August 9). Gone with the wind: Beech Leaf Disease spreads in New England, but these CT scientists could halt it. New England Public Media.

https://www.nepm.org/2024-08-07/connecticut-beech-leaf-disease-new-england

Baisden, E. (2021, August 18). Trees of the trolls: Meet the American beech. Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens. https://www.mainegardens.org/blog/trees-of-the-trolls-meet-the-american-beech/

Chen, Anelise. (2023, December 4). A Beech Walk on the brink. Arnold Arboretum. https://arboretum.harvard.edu/stories/a-beech-walk-on-the-brink/

DeSanctis, M. (2022, November 30). Yes, bears were everywhere in New England this year. Sierra Club. https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/yes-bears-were-everywhere-new-england-year

Funk, A., & Burke, D. (2024, May 22). Beech Leaf Disease Research update: The impact on microbial communities. Holden Forests & Gardens. https://holdenfg.org/blog/beech-leaf-disease-research-update-the-impact-on-microbial-communities/

Ida, H. (2021). A 15-year study on the relationship between beech (fagus crenata) reproductive-organ production and the numbers of nuisance Japanese black bears (ursus thibetanus japonicus) killed in a snowy rural region in central Japan. Landscape and Ecological Engineering, 17(4), 507-514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11355-021-00472-9

Kish, R., James, P. M., Mariani, R. O., Schurman, J. S., Thomas, S. C., Young, E. N., & Martin, A. R. (2022a). Beech bark disease in an unmanaged temperate forest: Patterns, predictors, and impacts on ecosystem function. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/ffgc.2022.831663

Leduc, F., Chagnon, C., Moreau, G., Dumont, S., St-Jean, É., & Achim, A. (2024). American beech outgrows sugar maple at the sapling stage regardless of partial harvest intensity in northern hardwood forests. Forest Ecology and Management, 553. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4591185

Lynch, M. (2024, January 9). Beech trees face uncertain future. Adirondack Explorer. https://www.adirondackexplorer.org/stories/beech-trees-face-uncertain-future

Nevins, M. T., D’Amato, A. W., & Foster, J. R. (2021). Future forest composition under a changing climate and adaptive forest management in southeastern Vermont, USA. Forest Ecology and Management, 479, 118527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118527

Nbrazee, N. J. (2023, December). Beech Bark Disease. Center for Agriculture, Food, and the Environment. https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/beech-bark-disease

Nyland, Ralph D. (2020). Control or Consequence: The Plague of American Beech [webinar]. ForestConnect, Cornell University.

Shepherd, B. L., Burke, D. J., & Stuble, K. L. (2025). Fagus grandifolia growth and mortality a decade after the emergence of Beech Leaf Disease. Trees, Forests and People, 20, 100836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tfp.2025.100836

Winship, L. J. (2019, July 19). Of beech bark, bumps and bears. Hitchcock Center for the Environment | Education for a Healthy Planet. https://www.hitchcockcenter.org/earth-matters/of-beech-bark-bumps-and-bears/

I’ve always loved your writing and lately it’s taken on such a deeper flavor. I love stewing on the thoughts you present :) Thank you for sharing this!

I just moved onto a piece of forested land in Greenwood Maine and have been really concerned about the over abundance of Beech clones crowding out all the other plants trying to thrive here. We have a lot of Beech Bark Disease here and I’ve been trying to figure out how to best take care of the forest we’re now stewarding! Have you come across anything about managing a forest with infected beech?